Communication is challenging in the intensive care unit (ICU) because of the multiple fundamental aspects of critical care. One aspect is complexity. Critical care is very complex, with clinicians from multiple disciplines all working under pressure toward the same goal: healing critically ill patients while caring for their families. A second aspect is patient acuity. With high patient acuity and unstable physiological status, managing the overall clinical picture becomes more intense. A third aspect is uncertainty. Uncertainty is a constant in regard to outcomes, affects decision making, and adds to stress for all involved, including patients, families, and clinicians. The final aspect is ethical challenges. With increasing technology and treatment options, ethical dilemmas can occur frequently. High-stakes ICU decisions often involve life or death. These situations may be further complicated by a dynamic in which many deaths in the ICU occur after a decision to withdraw life-sustaining treatment. Because ICU patients are rarely able to participate in this level of decision making, the burden of decision making is placed on families. Communication in these situations becomes even more vital. Because of ethnic, cultural, spiritual, educational, emotional, and other differences, the family literally may not speak the same language as the critical care team, who may speak in various dialects using terminology specific to their discipline. Given all these elements, it becomes easier to understand how challenging ICU communication can be.

Communication is challenging in the intensive care unit (ICU) because of the multiple fundamental aspects of critical care. One aspect is complexity. Critical care is very complex, with clinicians from multiple disciplines all working under pressure toward the same goal: healing critically ill patients while caring for their families. A second aspect is patient acuity. With high patient acuity and unstable physiological status, managing the overall clinical picture becomes more intense. A third aspect is uncertainty. Uncertainty is a constant in regard to outcomes, affects decision making, and adds to stress for all involved, including patients, families, and clinicians. The final aspect is ethical challenges. With increasing technology and treatment options, ethical dilemmas can occur frequently. High-stakes ICU decisions often involve life or death. These situations may be further complicated by a dynamic in which many deaths in the ICU occur after a decision to withdraw life-sustaining treatment. Because ICU patients are rarely able to participate in this level of decision making, the burden of decision making is placed on families. Communication in these situations becomes even more vital. Because of ethnic, cultural, spiritual, educational, emotional, and other differences, the family literally may not speak the same language as the critical care team, who may speak in various dialects using terminology specific to their discipline. Given all these elements, it becomes easier to understand how challenging ICU communication can be.

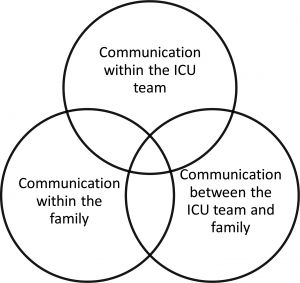

Three major challenges in ICU communication include challenges in communication among ICU team members, challenges in communication between the family and the ICU team, and challenges among family members. Each possible source of conflict has particular considerations and management strategies. This article reviews the evidence on each of these types of communication challenges as well as evidence-based interventions to address them.

Communication within the Critical Care Team

Evidence confirms that conflict is prevalent in ICUs all over the world. One study by Azoulay et al of 7498 ICU staff members across 323 ICUs in 24 countries found that 72% of participants perceived conflicts during the previous week, 53% of whom reported severe conflicts. Nurse-physician conflicts were the most common (33%), followed by conflicts among nurses (27%). The most common behaviors causing conflicts were personal animosity, mistrust, and communication gaps. Job strain was significantly associated with the perception of conflict, especially among those reporting more severe conflicts.

Several reviews on ICU conflict confirm similar findings. Fassier and Azoulay found that conflicts perceived by clinicians are frequent and mainly consist of intrateam conflicts. This review found that the main sources of ICU conflicts are end-of-life (EOL) decisions and communication issues. Conflicts reduced patient safety, patient- and family-centered care, and a critical care team’s cohesion and welfare. They also contribute to staff burnout and increased health care costs.

Given that critical care is delivered by a team, the team must communicate clearly. Ideally, the patient’s goals should be the focus of all care, and when the patient is unable to direct that care, the appropriate surrogate should provide the goals in the patient’s place. However, even when the patient’s or surrogate’s wishes are clear, communication issues may arise within the ICU team. The conflicts most often surround disagreements on prognosis and treatment plans. A study by Aslakson et al of a surgical ICU (SICU) found differences relating to opinions about prognosis between team members and surgeons. Satisfaction with communication about prognosis varied widely among the SICU nurses, surgeons, intensivists, and nurse practitioners. The SICU nurses felt that their comments were less valued by all providers.

Communication challenges between nurses and physicians are a common ICU issue, as per the previous reviews. In the SICU study by Aslakson et al, 43% of 2100 vascular, neurological, and cardiothoracic surgeons reported conflict with nurses in regard to postoperative goals of care. In addition, a survey of Canadian ICU nurses found that more than one third of conflicts were disagreements with nurses and the team. Nurse-physician/team conflict about EOL issues and goals of care are among the leading causes of ICU nurse moral distress, which affects team cohesion and morale. One study found that ICU nurses were caught between the need to provide information to patients’ families to ease their concerns and avoiding conflicts with physicians, who nurses felt would not want such information shared.

Communication issues between physicians also occur in the ICU. 8 Patients in the ICU are seen by multiple specialists, each with a different perspective and focus. Specialists may each comment differently on the progress or lack of progress of the patient from their perspective, and this conflicting information may lead to mistrust by the patient and the family as they try to understand the differing messages being delivered. Each perspective may be correct but may be limited in looking at the patient only through a specialty-focused lens. The SICU study by Aslakson et al 9 also highlighted the disagreement between surgeons and intensivists. The surgeons reported regularly experiencing conflict with intensivists in regard to postoperative goals of care in patients with poor postoperative outcomes.

Communication between the Critical Care Team and the Family

Decisions around treatment, especially at the EOL, are a major source of communication challenges between the team and the family in the ICU. Curtis and Vincent found wide variability in decisions such as withdrawing life support depending on religious or cultural background. Luce found that the principal EOL conflicts occur when families insist on treatment that the team considers inappropriate or when families disagree with the treatment the team recommends. The international ICU conflict study by Azoulay et al found that the main perceived EOL conflicts involved lack of psychological support, absence of team meetings, and problems with the decision-making process.

The literature is consistent that ICU patients and families need and want clear and honest information about the risks/benefits of treatment and the patient’s likely prognosis. In one study of ICU patients and families, 93% wanted to know the prognosis, even if it was bad or uncertain. Their rationale was that they needed to prepare emotionally and practically. And, being fully informed is the foundation of the informed consent process.

However, evidence also shows that families are more dissatisfied with communication in the ICU than with any other care issue. As noted earlier, the patient’s goals should be the foundation of the ICU care plan. However, most patients are not previously known to the ICU team, do not have advance directives, or have not told their loved ones of their wishes in advance. This lack of communication places a significant burden on patients’ families to attempt to infer what those wishes would be. The critical care team and families come to serious discussions in the ICU with different expectations based on religion, race, culture, and geography. Life and death decisions raise moral and ethical issues, and team members and families may not always agree on what is the right thing to do. Varying perspectives may exist in terms of culture, and nurses particularly find themselves negotiating with family members who are culturally diverse. Spiritual beliefs can be a factor, with some families believing that all life is sacred, no matter the quality. These spiritual beliefs may conflict with the team’s concept of medical futility. Most critical illnesses are sudden, and families rarely have time to prepare emotionally or practically. They may have no previous experience with the ICU and so are easily overwhelmed by that environment. They also may have unrealistic expectations about their loved one’s ability to fully recover, expectations that often are not overtly addressed by the health care team. In addition, families may have poor health literacy.

Communication can be further hampered by the team’s use of medical jargon or a team member’s lack of communication training. In teaching hospitals, often the junior, less experienced members of the medical team have the most contact with the family. Then, the rotation of critical care staff can undermine communication and any relationships that may have formed with the family. Attending physician A may be a wonderful communicator, helping to prepare the family for a poor outcome, whereas attending physician B has a different opinion about the patient’s prognosis and resists directly engaging with the family. Advanced practice nurses (APNs), because of their experience as nurses caring more closely for patients and families, may be better suited to interact with family members of ICU patients. A recent systematic review by Jennings et al of APNs in the emergency department found that they were rated higher on overall quality of care and patient satisfaction than medical providers.

Finally, the team and family can have different perceptions of whether communication issues even exist. In a study by Frost et al of conflicts between physicians and surrogate decision makers, agreement on whether conflict was present was poor, and physicians perceived less conflict than the surrogates. Surrogates were more inclined to perceive conflict when they felt discriminated against and less so when they were satisfied with the physicians’ bedside manners.

Communication Challenges within the Family

As noted earlier, critical illness often is unexpected, and thus, families are thrust into a situation of great stress and uncertainty, which affects their ability to communicate with each other. Day et al found that most family members of ICU patients experienced moderate to severe sleep disturbance and fatigue and mild anxiety. Some family members may experience posttraumatic stress disorder from a loved one’s ICU stay, and a 2014 literature review of studies on posttraumatic stress disorder among family members of ICU patients found several predisposing factors: family members who were in the decision-maker role, female gender, being the parent of the ICU patient or the family member of a younger ICU patient, having a high school education, and a history of psychological treatment. Some families pull together under these trying circumstances and are able to make difficult treatment decisions together. Others, however, struggle as previous family issues interfere with cohesiveness in this crisis situation. The ICU may not have additional interdisciplinary staff, such as social workers, chaplains, or palliative care resources, to help intercede with families who are struggling.

Family roles and routines are upset by critical illness. The patient may have been the matriarch or patriarch of the family, and without her or him to make decisions, the family may be disorganized. Often financial concerns arise about the cost of care or the loss of the patient’s or family’s income. Although many ICU patients are older and retired, in a study by Griffiths et al, 40% were employed at the time of their ICU admission. Of those patients, 32% reported a loss of income in the 6 months after their ICU stay.

Local family members may be closer to the reality of what the patient’s recent condition has been, whereas out-of-town relatives may have unrealistic expectations based on a past visit. Relatives who have strained relationships must now make decisions jointly on the patient’s behalf. In the absence of a previously designated decision maker, state law allows for surrogates, usually starting with spouses and then adult children. However, if there are multiple adult children or siblings, laws may not specify which family member is in charge, so they may need to make decisions as a group.

Interventions to Improve Communications

Evidence-based interventions can improve communication for these types of interactions. Implementing these interventions will not eliminate communication challenges but instead may help either reduce or resolve them.

Interventions to Improve Communications within the Critical Care Team

Several things can improve communication within the critical care team. Ideally, ICU clinicians should practice in an environment that promotes respect, professionalism, and civility. Magnet institutions, as designated by the American Nurses Credentialing Center, and Beacon units, designated by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, are recognized for promoting nurse-friendly and healthy work environments. Implicit in an environment that promotes respect is developing an appreciation for different perspectives in regard to religion, race, culture, or geography. The US population is becoming increasingly diverse; therefore, all clinicians should have education and training about cultural competence to be sensitive to different perspectives with their colleagues, patients, and families. Another area of training should include communication education, particularly for difficult conversations, because many clinicians may not have ever had such training. All critical care staff should be educated on basic palliative care concepts, such as symptom and pain management, cultural and spiritual assessment, family meetings, and EOL care. 15 In addition, ICUs should have processes for regular interdisciplinary forums or routine unit-level meetings.

The international conflict study by Fassier and Azoulay identified some practical areas to reduce conflict, such as ensuring that staff does not work more than 40 hours per week, or that provider and nurse staffing is adequate. One simple intervention is the use of a daily goals sheet or interdisciplinary rounds to ensure that the whole team knows and can contribute to the plan of care.

Although evidence on APNs in the ICU is limited, a study by Robinson et al found that nurse practitioners were seen to be helpful at promoting a team environment, communication, and addressing patient or staff concerns. In addition, APNs can take responsibility to improve communications with their colleagues. When a disagreement occurs, the APN should take the opportunity to reflect on the situation, attempting to see things from all perspectives. Often, conflict occurs more over interpretation of someone else’s comment or behavior rather than the comment or behavior itself. If the issue warrants follow-up, the APN should approach the individual in question and discuss the situation respectfully, professionally, and, ideally, in private. The goal should be to see if the individuals can find common ground, with the recognition that all parties usually want what is best for the patient, although they may not agree on what that is. Unprofessional, rude, or inappropriate communication should not be tolerated and may require follow-up with the nurse manager, fellow, or attending physician. However, the goal should always be to try to resolve things with the individual first, before going to the appropriate clinical leader.

Interventions to Improve Communication between the Team and the Family

Clinicians in the ICU should practice not only patient-centered care but also family-centered care. Such care not only benefits patients and families but also creates a better environment for all. Critical care nurses recognize the importance of having clear, consistent, and honest communication with patients and families, especially when conflict occurs within the team or between the team and the family. However, developing such communication takes effort. Interventions that have improved communication with families of patients in the ICU include providing simple printed information that orients the family to the ICU team and environment, and consulting an ethics or palliative care service if disagreements occur. These interventions can potentially reduce family emotional distress, treatment intensity, and length of stay in the ICU. Evidence shows that having a formal multidisciplinary family meeting within 3 to 5 days of an ICU admission and then every 3 to 5 days thereafter can improve communication about goals of care, lead to earlier decisions about whether to start or withdraw life-sustaining technologies, and reduce conflicts between the critical care team and the family. A review by Levin et al of the benefits of family meetings notes that because most deaths in the hospital take place in the ICU, EOL palliative care and withdrawal of life-extending treatment are predictable and should not be handled as unexpected emergencies. Communication with the family is also a process, not a single event, as the patient’s status, prognosis, goals, and treatment options change over time; therefore, ongoing communication with the patient or family is key. Finally, involving palliative care teams or resources sooner rather than later can help clarify goals of care and possible ethical or family issues upfront. Palliative care team members also can serve as mediators or facilitators between the ICU team and the family if communication problems or significant disagreements occur.

If a patient or family has been given all the necessary information and is competent to make a medical treatment decision yet chooses a course that the team disagrees with, the team must support and respect that decision. No one outside the patient or family really knows what is right for the patient, and the family will have to live with the consequences of any decisions they make for the rest of their lives. Too often the team offers treatment that is likely inappropriate for the patient, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and then is upset when that treatment is chosen. The solution is not to question such choices, but to avoid offering inappropriate options in the first place.

Policies such as open visitation or family visitation during rounding also improve communication between the team and the family. These policies are now being promoted by professional organizations such as the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses and the American College of Critical Care Medicine, and evidence shows that 85% to 100% of families would prefer to be present at rounds to have increased access to information. The ICU teams can be resistant to include families in rounds, but the evidence shows that family presence does not significantly increase teaching time, and teaching time might actually decrease.

From a nursing standpoint, simple things can be done to reduce potential communication conflicts with the family, including early identification of who the family is. Advanced practice nurses should include questions about the key people in the patient’s life in their histories, recognizing that some family decision makers might live far away or be estranged from the patient. Key players in the patient’s life also could include domestic partners/life partners as well as an identified health care surrogate who may be a close friend rather than a blood relative. The role of a court-appointed guardian can be reviewed here as well. If the patient is no-communicative and the family is present at the hospital, the APN should explore whether the patient had previously expressed any wishes about medical treatment and share those wishes with the full critical care team. Advanced practice nurses should involve social workers and chaplains in appropriate cases, and those resources also can help mediate between the team and the family, if needed. In practice, particularly the chaplain role should be involved to provide spiritual support and someone to listen to feelings expressed by the family. Finally, APNs should ensure that any important information they have learned about the family is included along with the medical information for any transitions the patient may have in the hospital or on discharge. This process may involve adding a specific section on the family to the ICU discharge or transfer note.

Despite interventions to promote improved communication with the family, some families continue to demonstrate maladaptive coping, which is usually driven by emotion, as opposed to reason, and can include impulsivity, denial, emotional venting, and the misuse of substances such as alcohol or drugs. Signs of maladaptive coping are maintaining firm denial despite clear information to the contrary, being unable to make any decisions, or demanding treatment that is clearly inappropriate. One approach with such families is to limit their choices to a narrow range of medically and ethically acceptable options. It is not a legal or ethical requirement that all possible medical interventions be offered to every patient in the ICU. Instead, each treatment should be recommended on the basis of its likelihood of meeting the patient’s medical goals while minimizing harm to the patient. Limiting options and holding firm on those limits can be challenging for critical care providers but, with the assistance of palliative care, ethics, social work, and/or a chaplain, can be maintained with families struggling to make decisions. An APN who is compassionate but firm about not offering treatments of limited benefit may find that families.

Interventions to Promote Communication within the Family

Many of the interventions covered in the previous section also can help the family with its own internal communication challenges or coping. The APN should assess the family members for their understanding and coping mechanisms and, if needed, call in other resources such as social work or chaplains to assist in providing family support. These resources can help struggling families establish support systems, so that they can better face a critical illness and the difficult decisions that may need to be made. Palliative care teams also are suited to providing such support, as they have the skills and the time to spend with families who are struggling. However, all critical care APNs should have psychosocial assessment and basic communication skills, because additional resources are not always available. Key communication skills include the ability to perform active listening, provide presence, and exhibit compassion toward patients and families. Often, no one has taken the time to find out why the family is fighting or angry. Just listening and validating emotions often can diffuse challenging interactions. Chaplains can be of great help in such situations.

Conclusion

Communication will always be challenging in the ICU in all 3 spheres, but various personal, educational, and systems interventions can make communication more effective. These efforts all have the common goal of providing patient- and family-centered care and of knowing, honoring, and respecting an informed patient’s or family’s wishes. Critical care APNs have an enormous role to play in this area, and when in doubt, using therapeutic communication and compassion will always be appreciated.

Ref:Grant M., Resolving Communication Challenges in the Intensive Care Unit, AACN Advanced Critical Care, 2015: volume 26, 123-130