The history of intensive care

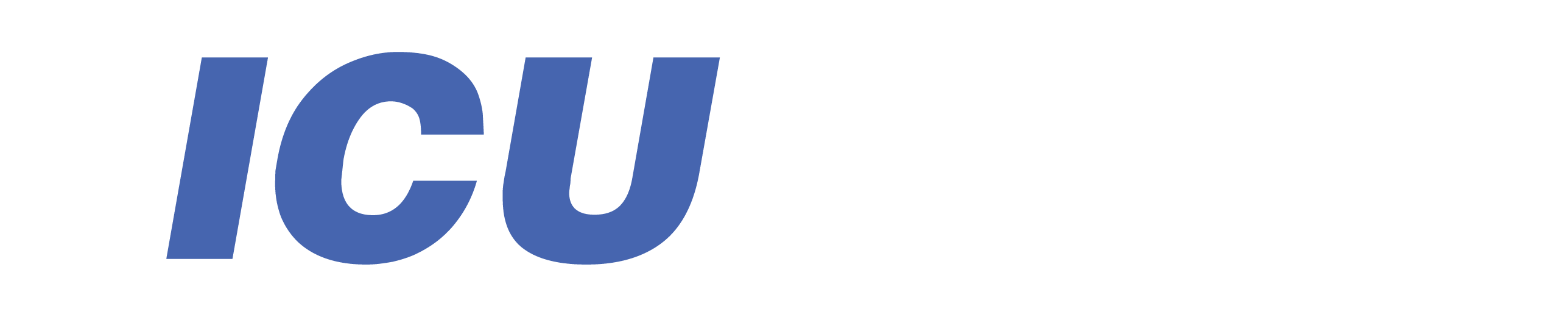

The polio epidemic in Copenhagen resulted in 316 patients developing respiratory muscle paralysis and/or bulbar palsy, with subsequent respiratory failure and pooling of secretions. The Blegham Hospital, the hospital in Copenhagen for communicable diseases, had only one tank respirator (Fig 1) and six cuirass respirators (Fig 2) at the time. This was completely inadequate to support the hundreds of polio patients with respiratory failure and bulbar palsy. The mortality rate from polio with respiratory failure and bulbar involvement was historically 85–90% and, as the epidemic progressed, the situation looked desperate.

Fig 1. Coventry alligator iron lung.

Fig 2. Cuirass shell ventilator.

Professor Lassen, chief physician at the Blegdam Hospital, had a strong desire to provide treatment for all polio victims, despite insufficient respirators, and therefore consulted with Dr. Bjorn Ibsen, a Copenhagen anesthetist. Professor Lassen hoped that positive pressure ventilation, as used in modern anesthesia at that time, might be a solution. Two days later, a 12-year-old girl with polio and resultant respiratory failure and bulbar palsy had a tracheostomy formed just below the larynx: a rubber cuffed tracheostomy tube was inserted and positive pressure ventilation successfully delivered manually with a rubber bag (Fig 3). Tracheostomies had been performed in Copenhagen for 4 years before this, but with little beneficial effect on outcome.

Fig 3. An 8-year-old girl being hand ventilated via a tracheostomy

As a result of this success, it became possible for the medical team in Copenhagen to treat potentially every patient admitted with polio. At the height of the epidemic, over 300 such patients were admitted per week, 30–50 per day, with approximately 10% either ‘suffocating or drowning in their own secretions. At times, there were over 70 patients in the hospital requiring respiratory support. Teams of medical students were drafted in and paid £1.50 per shift: 250 medical students came in daily and worked shifts with 35–40 doctors. By using such a strategy, mortality from polio in Copenhagen decreased from over 80% to approximately 40%.

Dr. Ibsen had the idea of caring for all such patients in a dedicated ward, where each patient could have their own nurse. Thus, in December 1953, the specialty of intensive care was born.

Dr. Henning Sund Kristensen took over the running of this Copenhagen intensive care unit (ICU) following the epidemic; many patients did not regain respiratory function and required long-term ventilation. Adjusting such ventilation, using blood gas analysis, was made possible by the invention of the first pH, pCO2 and pO2 electrodes by Astrup, Siggard-Anderson and Severinghaus. That the technology of pH monitoring was developed by the Danish brewing industry and, in particular, by the Carlsberg factory in Copenhagen, greatly helped Dr. Kristensen and his team. This, together with regular involvement of physiotherapists, improved survival rates further for patients requiring long-term ventilation. It rapidly became clear that teamwork was a vital component of high quality intensive care.

Max Harry Weil is considered widely as the ‘father of modern intensive care’ – he established a four-bed ‘shock ward’ at Los Angeles County/University of Southern California Medical Center in the USA during the early 1960s. During the 1960s and 1970s, ICUs were established in the UK. This was aided by rapid expansion in consultant anesthetists during the late 1950s, together with an increase in junior anesthetists who could staff such units around the clock. In the UK, the first full-time intensive care clinician was Professor Ron Bradley, who ran the ICU at St Thomas’ Hospital, London. This ICU, known as Mead Ward, had initially been set up by Dr. Geoffrey Spencer in 1966. Professor Bradley worked there with Dr. Margaret Branthwaite, who herself went on to lead the ICU at the Royal Brompton Hospital, and together they developed the first pulmonary artery catheter. The first microprocessor controlled ventilator was developed in 1971 and this, along with the development of a multitude of new equipment and drugs, stimulated a rapid growth of intensive care medicine.

Over the following 20 years, the specialty grew into the multidisciplinary discipline that it is today, with dedicated ICU nurses, physiotherapists, pharmacists, dieticians, technicians, radiologists and microbiologists. A specifi c scoring system, the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, or APACHE II score, was developed during the 1980s; this enabled case-mix adjustment, which was essential when comparing cohorts in research studies. In the UK, the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC) was established in 1994. From 2000, the number of high dependency unit (HDU) beds started to increase, the concept of outreach teams and follow-up clinics started, and difficult ethical decisions became increasingly common.

Developments over the past 10 years

The ability to support temporarily and, in some cases, replace the function of multiple-organ systems in the face of critical illness and injury is the core capability that underpins intensive care medicine. As a result, medical interventions in intensive care are more numerous and more invasive than those in the general ward setting, and the physiology of the critically ill patient is often fragile. This leaves ICU patients particularly vulnerable to iatrogenic harm.

More recently, there has been a ‘less is more’ shift in many intensive care interventions. Lung protective mechanical ventilation strategies, using lower tidal volumes and lower peak and plateau airway pressures, cause less injury to a patient’s lungs. Supra normal oxygen values are now considered harmful, although recent evidence supporting this in patients who have had a cardiac arrest is controversial. We accept lower mean arterial blood pressure and cardiac output values than we did 10 years ago. Patients are sedated less heavily than they were in the past, with the aim of keeping them comfortable instead of comatose, and daily sedation holds are undertaken where possible. We transfuse less blood and it has been suggested that we should give less nutrition.

A culture of quality improvement has become standard, with more reliable care, the use of care bundles and ‘doing the simple things well’ to make patient care safer. Care bundles are groups of four to five measures that, when performed together, have been shown to improve outcome: the two most established care bundles in intensive care concern the care of the ventilated patient and the central venous catheter (CVC). Previously, hospital-acquired infections were common in ICU patients because of their reduced immune system function, use of multiple catheters and cannula, and treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics. A dramatic decrease in such infections has occurred throughout the UK and elsewhere in the world.

Ventilators have improved considerably over the past 10 years. Previously, a patient needed to generate a pressure drop within the ventilator circuit to trigger a breath from the ventilator. In more modern ventilators, inspiration is typically triggered by a subtle change in flow, which is more sensitive and makes ventilatory support more comfortable for a patient. As a result, ICU patients tend to need less sedation than in the past. Pre- and post-cardiac arrest care has undergone major changes since 2000, and it is now common to cool out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors at 32–34°C for 24 h.

There has been an increase in large, multicenter intensive care trials that are not industry funded, which undoubtedly has contributed towards an ever-increasing drive to raise standards of care. Survival for intensive care patients in the UK has been improving year on year, with ICNARC twice recalibrating its risk prediction model because of increasing survival rates (personal communication, ICNARC data on file). This improvement is despite a trend to admit patients with more comorbidities to intensive care, as patient, family and even medical expectations rise. Ethical issues are common in ICU because patients are often unconscious and, therefore, legally incompetent, and because decisions made by intensive care doctors have immediate consequences.

Finally, possibly the most important change in the UK has been the establishment of intensive care as a stand-alone specialty, with the birth of the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine (FICM) in 2010. A stand-alone training program started in August 2012, and this should make intensive care training more accessible to trainees from respiratory medicine, renal medicine, cardiology and emergency medicine, as well as from the more traditional route of entry via anesthesia.

Ref: Kelly FE, Fong K, Hirsch N, Nolan JP, Intensive care medicine is 60 years old: the history and future of the intensive care unit, Clin Med (Lond). 2014 Aug;14(4):376-9